|

|

|

The UMD Hypersonics Club designed a “wave-rider” that gains lift from a shock wave generated along its leading edge, allowing for greater speed and range. Images provided by the UMD Hypersonics Team/Nick Purswani. |

|

FLIGHT AT HIGH MACH LEVELS HAS BEEN A LIMIT-DEFINING ENDEAVOR FOR GENERATIONS OF ENGINEERS. NEW TOOLS AND TECHNOLOGIES ARE PUSHING THE LIMITS.

The Department of Aerospace Engineering's annual magazine.

- Alumni Feature: Kevin Bowcutt: A Hypersonics Pioneer Who Launched His Career at UMD.

- Student Story: Hands-On Hypersonis: UMD's New Hypersonics Club Introduces Students to the Field.

For more than eight decades, aerospace engineers have explored the possibilities, and the challenges, of flight at speeds significantly greater than the speed of sound. Research into hypersonic flight, defined as five times the speed of sound or greater—that is, Mach 5 and above—began during World War II. The first successful hypersonic flight took place after the war’s end, in 1949, when the U.S. launched a two-stage sounding rocket that reached Mach 6.7. A series of milestones followed, involving both the U.S. and its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union: the X-15 aircraft, Yuri Gagarin’s 1961 flight, and development of the ballistic missile.

The University of Maryland (UMD) entered the arena in a big way in the 1980s, in large part due to the efforts of Professor John Anderson, Jr. At the time, the field had entered a lull, with interest dampened by the high costs involved as well as the difficulty of testing equipment at such speeds. Anderson, one of only a few academics with an interest in hypersonics, sensed the time was ripe for revival, and his instincts proved prescient. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan committed the U.S. to research that could produce what he called a “new Orient Express”—a plane that could depart from Dulles Airport, cross the Pacific at 25 times the speed of sound, and land in Tokyo two hours later. Reagan’s vision led to the National Aerospace Plane project, in which Rockwell International set out to engineer a vehicle, known as the X-30, that would take off like a plane. achieve low-earth orbit, and return to earth after completing its mission, whether civilian or military.

The buzz surrounding the initiative sent reporters scrambling to find experts who could explain it. They found one of the few who could—Anderson—at UMD.

In fact, Reagan’s “new Orient Express” never became reality; the X-30 program ended in 1993 without a prototype, a casualty of budget cuts and technical conundrums. However, it provided the impetus for later, successful projects undertaken by NASA and the Department of Defense: the X-43 and X-51. UMD alum-nus Kevin Bowcutt ’82, M.S. ’84, Ph.D. ’86, a student of Anderson’s, helped engineer both of these history-making aircraft.

Today, interest in hypersonics has gained fresh momentum, fueled in part by advanced computing and machine learning. These capabilities make it increasingly possible to solve engineering challenges and optimize designs before any actual tests are conducted. Because cost has proved a recurrent obstacle in hypersonics, these 21st-century tools promise to be game-changers.

UMD, meanwhile, continues to build on the legacy established by Anderson, now a professor emeritus. A new generation of researchers, including Christoph Brehm, Johan Larsson, Stuart Laurence, Pino Martin, and Gianna Valentino, is leveraging calculation-based, as well as experimental methods, to push the hypersonics envelope, support the development of new aircraft and space vehicles, and train the next generation of hypersonics experts. In the following sections, we’ll take a closer look at their efforts.

A Question of Flow

Hypersonics research has many facets, and one of the most important is the study of fluid flow. Put simply, flow is the movement of air (or other fluids, such as gases or water) around the parts of a vehicle, including control surfaces such as wings. For an aircraft to fly properly, engineers must understand the flow fields it will encounter and how these create lift and drag. They must also understand how the fields can interact with the materials of the vehicle, notably by generating heat.

Olive Oil or River

Engineers study two distinct kinds of flow, known respectively as ‘laminar’ and “turbulent.” The first of these is relatively straightforward; the latter mathematically complex and harder to predict. As UMD Professor Johan Larsson explains, laminar flow is smooth and predictable, like moving a toothpick through a teacup filled with olive oil. “It’s a regular pattern, without eddies,” he said. Compare that to the flow in a river: a branch tossed into it will move in chaotic ways, carried along by the swirling waters.

Such is the nature of turbulence. Turbulence is associated with higher levels of friction, which in turn produces heat. At subsonic levels, these processes are fairly straightforward and well understood. That’s far less the case with hypersonic flight, in which heat transfer can rise dramatically. And because turbulent flow is so volatile, with rapid changes in density and viscosity, accounting for it is no simple matter. Larsson, a mechanical engineering faculty member and affiliate of the Department of Aerospace Engineering, specializes in developing sophisticated computer models that can predict the effects of turbulence at hypersonic speeds with the accuracy needed to ensure reliability and safety. To do so, he leverages the advanced capabilities of supercomputers such as the Zaratan cluster at UMD. His colleague Christoph Brehm, associate professor of aerospace engineering, uses similar tools, but with a somewhat

different focus. While Larsson hones in on turbulence, Brehm is interested in how, when, and why one form of flow morphs into the other; that is, in the transition between laminar and turbulent flow.

A Breakthrough in the Study of Flow Transition

All moving vehicles, whether on the ground or in the air, generate both kinds of flow, with laminar at the front becoming turbulent at some point along the vehicle’s surfaces. For decades, engineers have puzzled over the exact mechanisms that spur the transition. It’s an important question because turbulent flows generate heat, and at hypersonic speeds this heat can be dangerous. In 2003, seven astronauts died when thermal protection on the Columbia Space Shuttle failed, leading to catastrophic damage during reentry.

Researchers know that some sort of initial fluctuation is needed in order to trigger a flow transition. As Brehm explains, “if there’s no disturbance anywhere in the system, the flow will remain laminar forever.”

But what causes that fluctuation in the first place? Is it because of the vehicle’s vibrations? Could it be connected to surface roughness? Brehm and his research collaborators may have found the answer, and it has to do with tiny bits of matter known as particulates.

Not just tiny, but micronsized. Brehm is one of the only hypersonics researchers in the world to have studied them. His calculations suggest that these miniscule bits of matter introduce disturbances that can trigger the transition to turbulent flow. “We’ve found that micron particulate is the root cause,” Brehm said. “It’s a very exciting discovery.”

To arrive at these results, Brehm used experimental data to create a model that simulates the flow around a vehicle. He then examined what would happen to the flow if particulates were added. It turned out that the location of the added particulate closely matched the transition front, that is, the line where one type of flow morphs into the other. That strongly suggests a relationship between the two phenomena.

Computers Reduce Need for Prototypes and Test Flights

The work being done by Brehm and Larsson helps streamline the design and production process for hypersonic vehicles, allowing many of the engineering problems to be identified and addressed early on.

Notes Larsson: “You want to compute lift and drag, for instance, and want to adjust your design so it’s aerodynamically stable. Much of this can be done on a computer.”

“Then, by the time you actually build a physical prototype, you’re pretty sure that it’s going to be reasonably close to the final product. All of this speeds up design and makes it more affordable.”

In general, Larsson said, engineers and manufacturers want to avoid having to build physical prototypes whenever they can. Prototypes cost both time and money to build; using fewer of them can speed up development and keep projects within budget.

The same principle applies not only to aerospace engineering, but to any type of machine that is affected by flow.

“Cars, convection ovens, refrigerators, even a coffee machine—in all these cases, you want to put the design into a super-computer and make predictions,” he said. “Only then do you start to build.”

Enhanced Capabilities: UMD’s New Hypersonic Wind Tunnel

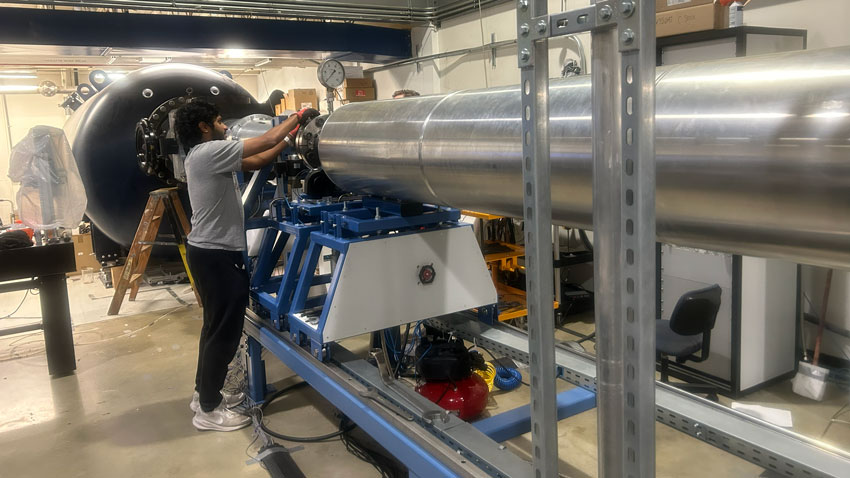

The experimental side of hypersonics research received a major boost with the recent completion of a new wind tunnel, housed in the A. James Clark School of Engineering’s Manufacturing Building. With a test section measuring 90 cm long and 60 cm across, it is significantly larger than previous hypersonic tunnels constructed at UMD. Funds provided in collaboration with the Army Research Laboratory (ARL) through a congressional grant are helping equip the facility with state-of-the-art diagnostic tools

Among other advantages, the new tunnel is designed to run longer- duration tests. “If we’re interested in testing flow interactions with structures over a relatively long time period, we can do so with this tunnel,” explains Aerospace Engineering Professor Stuart Laurence, who directs the research being conducted using the tunnel. Another plus is the ability to test models at Mach numbers of up to 8; most university facilities can only reach Mach 6 or lower.

Turbulence is one area where these capabilities come into play. Turbulent flows usually involve high Reynolds numbers. Aircraft can be affected by turbulence in a number of ways: greater drag could be produced, for instance, or the surface of the vehicle could be exposed to even higher levels of heating. In extreme cases, the effects of high-speed turbulence can affect structural integrity. With support from ARL and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), Laurence is using the wind tunnel to investigate a number of scenarios. “We’re looking at what happens when you have structures that can respond to the flow and potentially become coupled with that flow,” he said. “Turbulent flows will generate unsteady forces because of the pressure fluctuations within the flow field.”

“If you have a structure that is subject to those unsteady pressure fluctuations and starts vibrating, then those vibrations can feed back into the flow, and you can potentially have two-way coupling. This is quite a concern,” he said.

It’s of particular relevance to the U.S. Air Force, which has an interest in building reusable hypersonic aircraft but wants to make sure they can deliver reliable flight and avoid structural failure. The thin sur-face panels used on such aircraft can be prone to vibrations, which in turn could lead to structural fatigue. Advanced computing tools, combined with facilities like the hypersonics tunnel at UMD, are yielding a more complete understanding of the fluid dynamics and thermal processes involved, thus paving the way for practical solutions.

Related Articles:

Elon Musk Tweets Back

MATRIX Faculty to Present at International Conference

Dylan Hurlock Receives Wings Club Foundation Scholarship

New Initiatives Push Toward Safe & Reliable Autonomous Systems

UMD Students Sweep 2025 VFS Student Design Competition

Logan Selph Awarded NSF Graduate Research Fellowship

Gebhardt Named 2025-26 MWC ARCS Scholar

Rudolph Awarded Women in Defense Scholarship

Seven UMD Students Receive 2025 Vertical Flight Foundation Scholarships

Joseph Mockler Awarded DoD SMART Scholarship

February 12, 2026

|